How I Brought Mindfulness into My Special Education Class

For several years, I worked as a special education teacher with students with autism syndrome disorder. The first year was challenging to say the least. There were chairs thrown daily, bite marks, spit stains, and lots of tears. I needed to offer a lot more than just teaching reading and writing.

During my second year, I experimented with bringing daily mindfulness and yoga into the classroom. Honestly, it was a gamble, but we added mindfulness to our daily morning check-in. Less than a month later, there was a clear difference in my classroom. Of course, the chaos was not completely gone, but we saw students using the skills they learned during our mindful mornings throughout the day. I was shocked the first time I saw one of my clearly upset students walk over to a quiet corner, sit down, close his eyes, and start taking deep breaths.

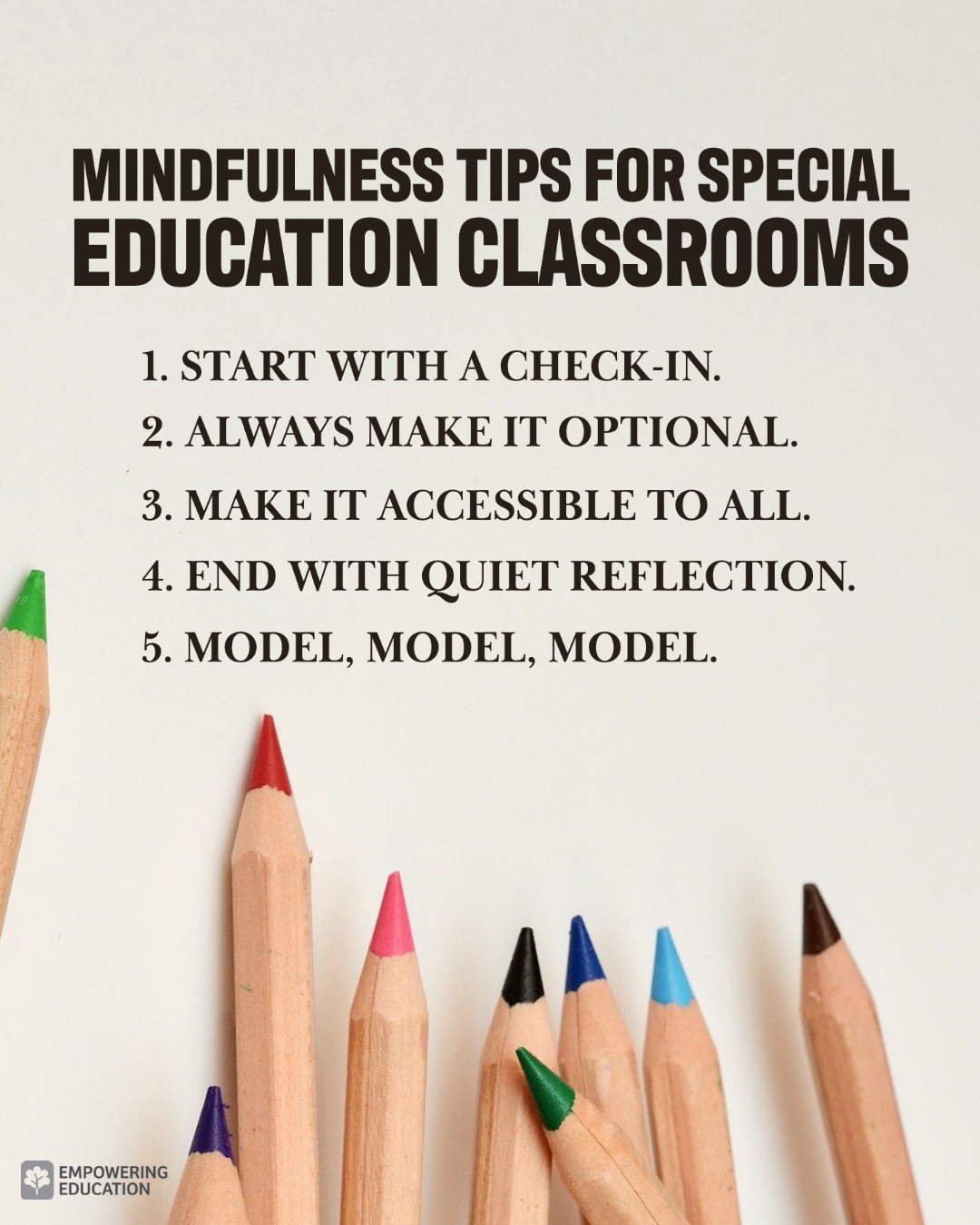

Here’s what I learned while incorporating a mindfulness practice into my special education classroom.

Start with a check-in.

Prior to having our mindful mornings, students would get right into their academic work. We changed this routine by starting with a mindful morning check-in. Sitting in a circle on the floor, we passed around a talking stick, and shared something about our day. Sometimes, it was about how we were feeling, our favorite food or color, or what we were sad about.

Not only did these check-ins show the adults in the room how students were showing up, but it also supported communication development, built eye-contact skills, and even practiced the fine-motor skills of passing a talking stick.

If students didn’t want to share, they were still expected to join the circle but could say “pass” when it got to them, practicing eye-contact and communication. After a few months, the students voted that you could only “pass” twice a week, because they wanted to hear how their classmates were doing.

Check-ins provided the staff with a chance to hear how each student was doing, which helped manage behaviors and expectations. If a student shared that they were having a rough morning, they were still held to the same standards of their peers, but they knew we heard them and could ask for extra support throughout the day.

Always make it optional.

Kids, and most adults, do not like to be told what to do. After our morning check-in, we would practice a breathing technique, a yoga pose, or even stillness. Whatever the mindfulness practice was that day, one of the adults would explain it, and then give students the option to participate. The students had the option of sitting at their desks, reading, or putting their heads down.

Offering choice was critical in building our mindfulness routine. Students didn’t feel pressured to do mindfulness, but even the kids who chose to sit at their desks would still practice mindfulness. For example, one student would usually sit at his desk with his head down during our mindfulness activities. About six months in, he started to do some of the movements and breathing exercises at this desk, but refused to participate with the whole class.

After six more months, this student was leading mindfulness in the mornings every chance he could. I strongly feel that because we gave him the time and space to get comfortable with mindfulness, he was able to adapt to the new practice on his own terms. As a result, this student used mindfulness as a coping skill daily. Towards the end of the school year, I would often see him go to a corner, facing a wall for some privacy, and practice one of the breaths or movement techniques.

Make it accessible to all.

Providing choice, but it is also an evidence-based practice for working with students impacted by trauma. For example, saying something like, “for this mindfulness, you can keep your eyes open or feel free to close them. Know if you close them, that I will have my eyes open.” This gives students a choice to close their eyes knowing they are safe if they do.

Another example of choice: let students sit where they want to when they’re doing mindfulness. For some students who have experienced trauma, sitting with their back against a wall may let them feel safer in a classroom especially if their eyes are closed.

For a class with unique physical needs, make sure there are options so all students can participate. Sometimes we’d do yoga with the breath, like raising our hands to the sky as we take a breath in and dropping them down as we breathe out. So that this practice is accessible to all bodies, make sure to give different choices (raise your arms, legs, or fingers). When all students feel that they can do the activity, they will more likely join in.

End with quiet reflection.

At the end of our mindfulness time, we always ended with 10–15 minutes of quiet reflection. Again, I emphasized choice, so that students could close their eyes, lie down on the ground, color, read, or simply look out the window.

For the staff who had paperwork to fill out, lessons to lead, and meetings to attend, quiet stillness took some time to master. For most, this time was the only moment where they were in complete silence with nothing to do.

At first, I would hear, “this is boring” from a few kids. After they got used to having some downtime with no screens, no adults talking at them, and no real rules to follow, those same kids would ask for more quiet time. Mid-year, other teachers and staff came to our room for that 15 minutes so they too could enjoy some quiet time.

Model, Model, Model.

Out of everything, I would say modeling was the most crucial. The paraprofessionals and I made it a point to model mindfulness with our class. Educators are busy, so it can be easy to check our emails, finish a report, or grab a snack while a paraprofessional runs mindfulness. However, when all the adults in the room modeled the morning routine, students felt safe participating. It also gave us as staff a moment of calm in the morning to get centered and ready for the day ahead.

As a special education teacher, I can look back on all the incredible teaching successes and losses, and I can honestly say that adding mindfulness to my special education classroom was one of the most beneficial things I did as a teacher. I was able to watch my students learn something new that they could use as a life skill and a coping tool when things get hard. It brought me goosebumps when I would watch one of my students boil up with frustration, and then be able to do one of the mindfulness exercises we had learned together to calm down.