The first two posts in this series defined trauma and then explained trauma in the context of the central nervous system. This post explores the long-term health impacts of early childhood trauma and revisits our original inquiries:

Remember: Everyone in the classroom has a story that leads to misbehavior or defiance. Nine times out of ten, the story behind the misbehavior won’t make you angry. It will break your heart.

—Annette Breaux

- Why is trauma more common in women and children?

Trauma is more common in women and children for the simple reason that these populations tend to have less capacity for solution (active response to threats) and are more frequently victims of domestic violence.

According to the American Psychological Association:“Research indicates that women are twice as likely to develop Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), experience a longer duration of posttraumatic symptoms, and display more sensitivity to stimuli that remind them of the trauma.” (Facts About Women and Trauma)

Children, as a population, have even less capacitity for solution. Consider a child living in an abusive household: what is their active response to threat? Are they physically capable of fighting back? Do they have the financial or cognitive resources to escape the situation? Do they have the coping skills needed to regulate their nervous system and return to a resting state? In short, do they have any viable solutions? Of course, the answer to these questions is almost invariably no, which is why the vast majority of trauma occurs in early childhood.

Children, as a population, have even less capacitity for solution. Consider a child living in an abusive household: what is their active response to threat? Are they physically capable of fighting back? Do they have the financial or cognitive resources to escape the situation? Do they have the coping skills needed to regulate their nervous system and return to a resting state? In short, do they have any viable solutions? Of course, the answer to these questions is almost invariably no, which is why the vast majority of trauma occurs in early childhood. - Why is trauma potentially one of the most costly and deadly public health concerns for our society?

Between 1995 – 1997 the CDC and Kaiser-Permanente conducted one of the largest investigations ever on childhood abuse and neglect – the Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACES). The initial study included medical examinations and in-depth mental health surveys on over 17,000 participants. The study has since been replicated with more diverse populations and the results have been nothing short of staggering.

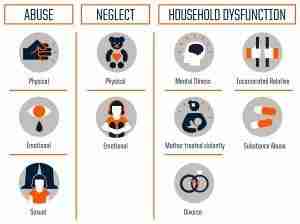

Regardless of the data source, almost two-thirds of participants reported having at least one adverse childhood experience (ACE) and more than one in five reported three or more ACE’s. ACE’s include events like physical, emotional, and sexual abuse; physical and emotional neglect; and household dysfunctions like mental illness, domestic violence, divorce, substance abuse, and incarcerated relatives.

As a person’s ACE score increases, so does their risk for the following:

According to the Adverse Childhood Experiences — ACE — study, the rougher your childhood, the higher your score is likely to be and the higher your risk for various health problems later. Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Credit: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation

Some of the more significant findings include:

- People with 6 or more ACE’s:

- Were likely to die 20 years earlier on average

- Had a 4,600% increase in the likelihood of injected drug use.

- People with 4 or more ACE’s:

- Had a 460% increase in the likelihood of depression

- Had a 1,220% increase in attempted suicide

- Had a 500% increase in rates of self-reported alcoholism

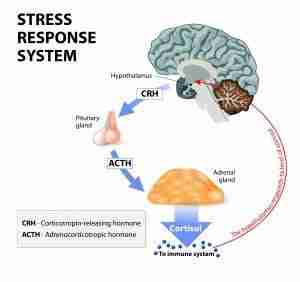

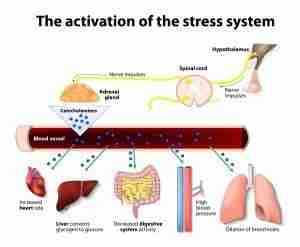

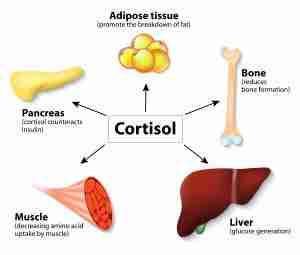

In short, people with more ACE’s were at significantly higher risk for a wide range of behavioral, mental and physical health issues – including the leading causes of death (heart disease, cancer, respiratory disease, stroke, obesity, addiction, and suicide). While it may not seem immediately apparent how traumatic childhood experiences could lead to things like cancer, stroke, obesity and broken bones – consider how chronic activation of the SNS and thus exposure to increased levels of stress hormones like cortisol could impact the immune system and a person’s overall well-being

Although this study has it’s limitations (it did not examine resilience factors like supportive relationships, quality health care, exercise, and nutrition, for instance) the results leave little question that early childhood experiences of trauma impact long-term health outcomes in a significant way. While inferring causation may seem like a stretch to some, it does not require a huge leap of imagination to see how trauma and adverse childhood experiences may indeed be at the root of many major public health issues like cancer, heart disease, stroke, addiction, and suicide.

If this is the case, one begins to wonder what might happen if our medical model were to shift from treating the symptoms of these illnesses towards the prevention and treatment of their root cause – trauma. The next post in this series will answer our final inquiry: How is mindfulness a viable solution for trauma?

Children, as a population, have even less capacitity for solution. Consider a child living in an abusive household: what is their active response to threat? Are they physically capable of fighting back? Do they have the financial or cognitive resources to escape the situation? Do they have the coping skills needed to regulate their nervous system and return to a resting state? In short, do they have any viable solutions? Of course, the answer to these questions is almost invariably no, which is why the vast majority of trauma occurs in early childhood.

Children, as a population, have even less capacitity for solution. Consider a child living in an abusive household: what is their active response to threat? Are they physically capable of fighting back? Do they have the financial or cognitive resources to escape the situation? Do they have the coping skills needed to regulate their nervous system and return to a resting state? In short, do they have any viable solutions? Of course, the answer to these questions is almost invariably no, which is why the vast majority of trauma occurs in early childhood.